Early Renaissance Sculpture

Just this week, I became reacquainted with this BEAUTIFUL head from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, probably from Flanders/Burgundy. Being half-Swiss I naturally gravitated in college to the study of the Renaissance in northern Europe.

I’ve been to many, many churches in Switzerland and have found some of the most amazing (sometimes) life-sized sculptures, including a Lamentation group in the cathedral in Fribourg. The reason this head from Albright-Knox struck me is that northern European Renaissance art is often denigrated when compared to what was going on in Italy during that “rebirth.” As you probably know by now, I’m not a big fan of Italian Renaissance art, because it is used by many art historians as a “measuring stick” in all other art, including non-Western art.

|

| Flanders, Unknown Artist, Head of Christ, early 1400s. Gessoed and painted wood, 11" x 7 5/8" x 8 3/8" (27.9 x 19.4 x 21.3 cm). © Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. (AK-800) |

There is not a strong tradition of freestanding sculpture in northern Europe during the Renaissance in Europe until the 1500s. The strongest tradition of sculpture in northern Europe came in the form of jamb figures in northern churches. Northern artists were not surrounded by the sculpture of ancient Greece and Rome, as were Italian artists of the period. Northern sculpture tended to continue the Gothic tradition of emphasis on the emotional / spiritual, rather than the physical.

That being said, I find northern Renaissance sculpture to be particularly compelling because of the emotional content, as opposed to the Italian Renaissance emphasis on classical balance and calm. This head of the crucified Christ, probably from a life-sized lamentation group, is particularly stunning in its realism and striking pathos (especially in the barely open eyelids). Wooden sculptures such as this were usually painted, often with a thin layer of plaster or gesso over the wood.

Ironically, this application of paint copies classical Greek sculpture more than Italian Renaissance renditions of their ideas of classicism in pure white stone or marble. Regardless of religious conviction, this head is profoundly beautiful in its carving, as much as I would admire the head of a bodhisattva or the Buddha from Asia.

|

| Tilman Riemenschneider (1460–1531, German), Saint Stephen, 1502–1510. Painted and gilt lindenwood, height: 36 1/2” (92.7 cm). © Cleveland Museum of Art. (CL-679) |

While Italian artists consciously attempted to reproduce the ancient Greek and Roman emphasis on the physical body (they had lots of nude sculptures to copy), northern artists emphasize a sort of expressionistic spiritual force. This was manifested particularly compellingly in German works in the Zackenstil (zig-zag style), that obsessed with pointed, often amazingly complex drapery, that effectively obscured most reference to the physical body underneath. Riemenschneider is one of my favorites who dealt with this. Notice in his Saint Stephen how there are very few references to the underlying body parts beneath the zig-zag drapery, although hands and face are treated very convincingly.

|

| Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455, Italy), Aaron, from the Gates of Paradise, Baptistry, Florence, ca. 1425–1452. Gilt bronze. Davis Art Images. (8S-12666) |

|

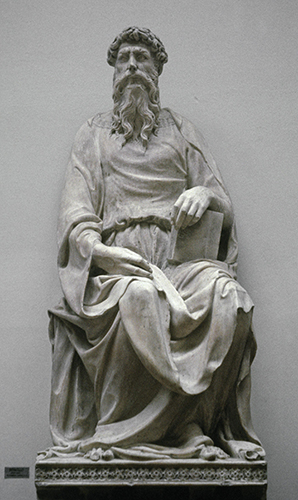

| Donatello (ca. 1386–1466, Italy), Saint John the Evangelist, 1408–1415. Marble, height: 82 11/16" (210 cm). Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence. (8S-5840) |

When we look at Italian works from the same period as the Head of Christ, we see striking similarities to the Riemenschneider of a century later. Ghiberti has certainly mastered the contra-posto (hipshot) pose from antiquity, and Donatello has certainly indicated the body masses beneath the robes similar to antique models. However in both artists’ work, the exuberant drapery of the Gothic period (c. 1200–1400) persists. And notice the similarity of the treatment of the beards on the two Italian examples compared to our Head of Christ. I wonder if one has to part a goatee and add curlers to achieve that look?

While the Flemish sculpture is certainly realistic, the Italian examples seem much more like portraits rather than interpretations of facial features. All in all, although I have an abiding love of northern European sculpture, I can’t say I like it more than the Italian examples from the same period. The art historian in me appreciates the qualities of both styles.

Correlations to Davis programs: A Community Connection: 3.2, A Global Pursuit: 4.4, Discovering Art History: 10.1, The Visual Experience: 15.8, Beginning Sculpture: 5

Comments