Chrysanthemum Day and Festival

I’ve shown this print on this blog before, but only in passing with other works concerning vacations. I’ve never gone into depth about a holiday that I think should be adapted around the world, Japan’s Kiku no Sekku, or Chrysanthemum Day (September 9). It is a national day, compared to the later Chrysanthemum Festival week that is celebrated at Buddhist and Shinto temples throughout Japan. Chrysanthemum Day was set on the date of the Chinese Double Nine Festival (ninth day of ninth month). Both events celebrate a treasured national symbol.

|

| Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815, Japan), Children at the Chrysanthemum Festival, from the series Precious Children of the Five Festivals, ca. 1795. Color woodcut print on paper, 15 1/8" x 10 1/8" (38.4 x 25.7 cm). © 2019 Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA-1743) |

The chrysanthemum was introduced into Japan from China during the Nara Period (645–794 CE). It became such a popular flower, especially with the imperial court, that the first Chrysanthemum Festival was celebrated in 910 CE by the emperor’s court. Ultimately, the flower became the symbol of the emperor and of Japan itself. The shape of the chrysanthemum was likened to the rays of the rising sun, the red circle on the Japanese flag. Because of its associations with the imperial family, which has traditionally been considered divinely born, the chrysanthemum has come to symbolize rejuvenation and longevity.

Kiyonaga’s print shows children preparing small gift boxes of chrysanthemum petals and blossoms as gifts during the Chrysanthemum Festival. It also shows them having a lot of fun doing it. The Japanese cultivated several types of blossoms of the flower, a couple of which this print depicts. There are a lot of varieties of the chrysanthemum.

Kiyonaga, the pupil of Torii School master Kiyomitsu (1735–1785), is most famous for his prints of attenuated, elegantly curvilinear figures of famous beauties (bijin ga) in the ukiyo-e genre. However, in the early 1790s he gave up that subject almost entirely to concentrate on genre scenes and painting. There is a decided emphasis on the middle class in such prints as this. Kiyonaga made sure to endow the figures with the same elegant qualities as his bijin ga. The children wear the most up-to-date fashions in kimono patterns, which are handsomely contrasted in the print.

|

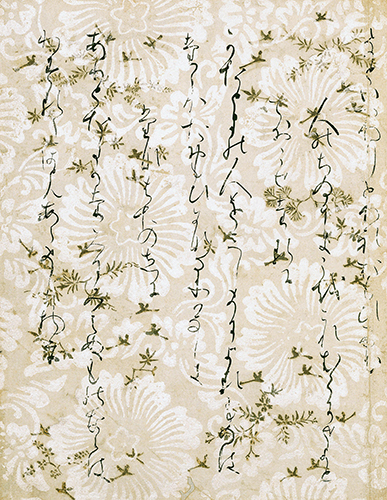

| Unknown artist (Japan), Leaf with a poem by Lady Ise (died 940 CE), from Anthology of Poems by Thirty-Six Immortal Poets, 1108–1122. Ink and silver leaf over mica woodblock printing on paper, mounted later as a hanging scroll, 8" x 6 ¼" (20.3 x 15.9 cm). © 2019 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2816A) |

This poem sheet, first woodblock printed in white ink on a mica ground in an abstract chrysanthemum pattern, is an example of how quickly the flower became a popular symbol in Japanese art. Also printed with the chrysanthemum are plum blossoms (in white), pine needles, bellflowers and maple leaves. This is but one of 190 poems thought to have been committed to paper by at least twenty calligraphers. The script is in the wayō shodō (Japanese calligraphy) style of cursive Japanese that was developed between the 800s and 900s CE. The richness of this work is an indication of why the Heian Period in Japan (794–1185) is often considered one of the earliest periods when all Japanese arts flourished.

|

| Utagawa Hiroshige I (1797–1858, Japan), Chrysanthemums, from a Flowers and Birds series, 1843–1847. Color woodcut print on paper, 13 5/16" x 4 5/8" (33.8 x 11.7 cm). © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-979) |

Speaking of the ukiyo-e style, naturally the most famous of landscape woodblock artists, Hiroshige, executed dozens of images of chrysanthemums during his career. They range from images of single blooms, close-ups of clusters of blossoms like still-life subjects, and settings in nature like this print. After the success of his landscape series starting in the 1820s with Famous Places in the Eastern Capital, Hiroshige decided to concentrate on landscape and scenes from nature like this. This format of Chrysanthemums evolved from the kachō ga (bird-and-flower painting) tradition of subject matter. Influenced by Chinese examples, it grew in popularity starting in the Kamakura Period (1185–1333).

|

| Japan, Kamakura Period, Box with chrysanthemum decoration, 1300–1333. Lacquered wood with gold leaf, 6 15/16" x 10 3/4" x 8 1/4” (17.6 x 27.4 x 21 cm). © 2019 Cleveland Museum of Art. (CL-282) |

Emperor Gotoba (1180–1239) chose the sixteen-petal chrysanthemum as his personal emblem, applying the flower design to his sword and everyday utensils. By the Kamakura Period (1185–1333), it was widely popular for decoration outside of imperial circles. Even the pull plate on the side of this box is formed in the shape of a chrysanthemum.

Lacquer has played an important role in Japanese art for at least 2000 years as a protective, decorative finish on wood, leather, paper, bamboo, and metal. It is formed from sap collected from the Rhus verniciflua tree (the “lacquer tree”). This box is decorated in the maki-e (sprinkled picture) technique, in which up to eight layers of lacquer are applied over numerous layers of metallic (gold) leaf.

Comments