A Bridge: Jasper Johns

The impression a reader gets from some surveys of art history, unfortunately, is that one artistic movement ends and another picks up in a totally different direction. We know this is not true when we see, for example, how classicist realism persisted in painting long after Impressionism hit the scene in the 1870s. The same is true with “movements” in modernism.

The more I learn about some artists the more I question the convenient categories into which they are often pigeon-holed. Many of the artists who pioneered abstraction in the early 1900s began their careers painting in either an Impressionist or Post-Impressionist style, because by that time, Impressionism had become almost institutionalized. The same goes for Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s in America. By the mid- to late 1950s it was practically academic in its dominance over modernism. Artists who eventually explored other forms of modernism in reaction to Abstract Expressionism were unavoidably influenced by it when they were developing their mature styles.

|

| Jasper Johns (born 1930, United States), Green Target, 1955. Encaustic on newspaper and cloth over canvas, 60" x 60" (152.4 x 152.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (MOMA-P1929jovg) |

Jasper Johns is perhaps most famous for his paintings and prints that feature images of the American flag or target, both obviously potent symbols of American culture (next to the dollar sign, I guess). This connects him to Pop Art’s explorations of representational imagery that emerged in the very late 1950s and early 1960s. But, I have just recently found it unfortunate that Johns’s name is so frequently only associated with Pop Art. Like many artists, Johns’s body of work is incredibly varied and complex, and I find it a bit irritating to merely link him to Pop Art because he used aspects of mundane American culture as subject matter.

Johns was born in Georgia and raised in South Carolina. He studied art at the University of South Carolina and Parsons School in New York in 1948. After service during the Korean War (1950–1953), Johns returned to New York, where he met another seminal artist of Pop Art: Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008). He and Rauschenberg, who was already using gestural painting as part of his work, formed a close association, inspiring and influencing one another’s art until 1961.

Rauschenberg ushered Johns into the art scene in New York, at the time dominated by Abstract Expressionism. The two artists worked together closely until the early 1960s, both acquiring from Abstract Expressionism the brush work of action painting, but little else. Little by little their work moved away from Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. Of major impact on both their bodies of work was a viewing of the Surrealist and Dada works, particularly the found object works ("readymades") of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1958. Johns's work expanded as he incorporated the painting technique of Abstract Expressionism and the incorporation of banal everyday objects into it.

These paintings from Johns’s early mature work show how he combined Abstract Expressionism’s painterly surface with something that was anathema to the Abstract Expressionists: reference to everyday objects or symbols. Ironically, Johns’s titles—Flag, Numbers, Target, and the like—do not leave the impression of any literary, symbolic, or romantic intent, even more anathema to Abstract Expressionists. They are merely convenient vehicles to contrast with the beautiful painterly surface. What I like the most about these early works is that, unlike the American flag, the reference to American culture does not hit the viewer over the head, it is so subtle. I am, no doubt, not the first art historian to consider Johns’s importance to lie in his being a bridge from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art. Interesting fact, make of it what you will: Johns once stated that he conceived of the American flag subject after dreaming about painting it.

Other “bridge” works:

|

| Jasper Johns, Tango, 1955. Oil and encaustic on canvas, 42 7/8" x 55 1/8" (109 x 140 cm). Private Collection. © 2015 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (8S-27041jovg) |

|

| Jasper Johns, Painting with Two Balls, 1960. Mixed-media, 64 15/16" x 53 15/16" (165 x 137 cm). Collection of the Artist. © 2015 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (8S-27050jovg) |

|

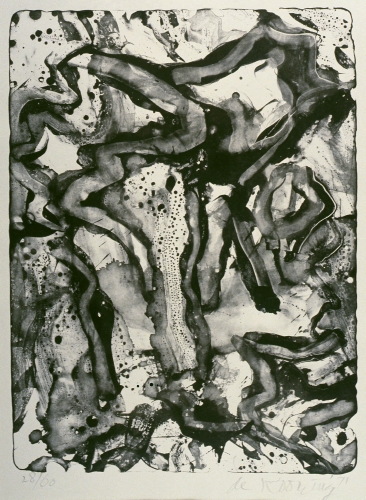

| Jasper Johns, False Start, 1962. Lithograph on paper, 18" x 13 3/4" (45.7 x 34.9 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. © 2015 Jasper Johns / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (AK-2200jovg) |

I personally love Johns’s lithographs, because I remember from school the joy of working with a litho stone and the textural possibilities involved. Lithography was a favorite medium of Willem de Kooning (1904–1997), one of the “action painters” of Abstract Expressionism. Look at how fluid de Kooning’s lithograph is! I’ve seen one of his lithographs in which he used a floor mop as a “brush!”

|

| Willem de Kooning (1904–1997, US, born Netherlands), The Preacher, 1971. Lithograph on paper, 29 15/16" x 22 7/16" (76 x 57 cm). Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH. © 2015 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (BIAA-44kgars) |

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 4 6.35, 6.35-36 studio; Explorations in Art 6 5.25; A Community Connection 6.2, 8.4; Experience Painting 7; Experience Printmaking 6; Exploring Painting 12; Exploring Visual Design 6, 8, 10; The Visual Experience 9.3, 9.4, 16.7; Discovering Art History 17.1, 17.2

Comments