An Autumn Idyll from Japan

One of the most fascinating things I learned (among many fascinating things) while studying Japanese culture and art when in college, was that Japanese scholars would routinely debate the virtues of an autumn over a spring garden, or vice versa.

I had an epiphany in this philosophical exploration once while I lived in Chicago, when I saw an ostensibly dead garden in November, with dried up chrysanthemums. A light snow had covered the dying blossoms and other brown aspects of the garden and I realized that my vote would be for an autumn garden! Just as I appreciate the way Luminist artists (of the Hudson River School) captured the essence of autumnal landscape color and light, Japanese artists are particularly adept at summing up, very succinctly, the essence of autumn.

|

| Sakai Hōitsu (1762–1828, Japan), Autumn Leaves and Chrysanthemums. Ink and colors on paper fan mounted as an album leaf, 6 3/4" x 19 3/16" (17.2 x 48.7 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-731) |

What more appropriate symbols for autumn than turning maple leaves and chrysanthemums. I just love mums, and, they are the official flower of Japan and a symbol of the imperial family. The Japanese liken the radial symmetry of the mum to the sun’s rays. And after all, who doesn’t think “autumn” when one sees mums?

This is a sedate piece for Sakai, who was the standard bearer for the Korin school of painting during the later Edo period (1615–1868). The Tokugawa military dictators (shogun) who ruled Japan during the Edo period virtually isolated Japan from the rest of the world. Japanese artists therefore looked to Japanese art of glorious periods from the past. The master Ogata Korin (1658–1716) “founded” the Korin school that further cemented the popularity of the Yamato-e style (meaning Japanese picture) of the Heian period (794–1185), considered the classic Japanese style.

Sakai was the leader of the so-called “Rinpa” school in the late 1700s and early 1800s. This comes from “pa,” meaning school, and “Ko[Rin]” for the founder’s name. Sakai was so enamored of Ogata’s style, that he studiously copied his works, often on the back of screens by the late master that he owned!

|

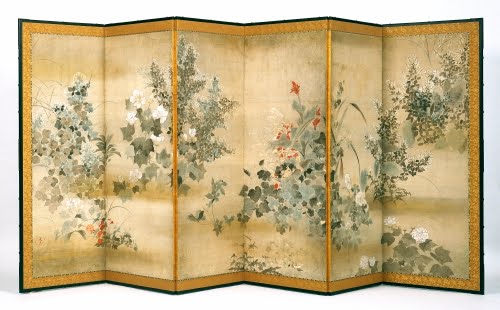

| Kitagawa Sosetsu (ca. 1620–ca. 1690), Autumn Flowers. Ink, color, and gold leaf on paper, mounted on wood as six-fold screen, 56 13/16" x 132" (144.3 x 335.4 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3022) |

This beautiful byobu (six-fold screen) displays autumn’s seasonal flowers, except for the chrysanthemum! Visible are ivy, bush clover, mallow, coxcomb, and grasses. Yamato-e imagery often seems to float on a vague background made all the more vague by the gold leaf. It’s easy to see why Impressionists gravitated to Japanese painting because of the spontaneity of composition. In fact, this screen was once owned by American Impressionist Mary Cassatt (1844–1926).

Yamato-e was the opposite of kara-e “Chinese picture,” symbolized by the Song Dynasty (960–1279/1280) classic style of monochromatic brush landscape paintings. With emphasis on dramatic composition, nature simplified to shapes, and extravagant use of gold leaf, screen painting of this period was truly Japanese in outlook.

Kitagawa Sōsetsu was a pupil of Tawaraya Sōsetsu, who was either a disciple or son of Tawaraya Sōtatsu (1576–1643), considered a founder of the school that specialized in the decorative yamato-e style, which led to such masters as Ogata Korin. Sosetsu's work is typical of this "first generation" of painters of the Rinpa style.

|

| Kanō Eisen’in Michinobu (1730–1790), Waterfall and Autumn Foliage. Ink and color on silk hanging scroll, 51 3/4" x 17" (131.5 x 43.2 cm). © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (MFAB-1326) |

There’s nothing I enjoy more than getting drawn into a landscape in the kara-e style. One of the actual goals of Chinese and Japanese landscape painting, established during the Song Dynasty in China, was for the viewer to be able to imagine taking a “stroll” through the painting. I really do like how Edo artists took the Chinese technique of mist to suggest depth to an almost abstract dimension.

Michinobu was one of a long line of painters who took the Kanō name from the founder of the Kanō School, Kanō Masanobu (1434–1530). Through the centuries the Kanō School was the favorite of the samurai and noble classes and was steeped in the tradition of monochromatic Chinese painting. During the early 1700s, the school’s style had adapted decorative, overly realistic nature painting in bright colors. This style was called Nanpin after the Chinese painter Shen Nanpin (1682–after 1762), who had introduced a more scientific approach to painting nature to Japanese artists.

Michinobu was one of the last great leaders of the Kanō School, who tried to return the school to the school’s Chinese-inspired roots. He was the son of Kanō Eisen Hisnobu (1698–1731), who had also led the school. It was traditional in Japan for artists to either be adopted by their mentor, or to take the name of the mentor as a badge of honor. Needless to say, from the 1400s to the 1800s there were a lot of Kanōs!

|

| Suzuki Harunobu (1725–1770), Autumn Moon in a Mirror, from the series Eight Parlor Views, ca. 1766. Color woodblock print on paper, 11 1/2" x 8 5/8" (29.2 x 21.9 cm). © Davis Art Images. (8S-4159) |

I couldn’t resist closing with a Harunobu. His prints are so charming and really show a lot about every day middle-class life in Edo Period Japan. This view of a maid fixing her boss’s hair is typical of the subtlety of Japanese art. Although the title alludes to the moon in the mirror, the moon is not visible. We can only imagine it. The only other hint that it is autumn is the cockscomb outside the window. Eight Parlor Views is an awesome series that shows the occupations of middle-class women in the household.

Little is known about Harunobu’s life or art education. The sophistication and elegance of his prints, however, may indicate that he came from a middle-class or samurai family. His prints followed the convention of the ukiyo-e style until he began producing the twelve-color (12 separate blocks of wood) prints after learning the new process in 1765.

Harunobu’s style of elegant, slender figures, both male and female, established a style that was emulated by artists who followed him, including Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815) and Utagawa Utamaro (1753–1806). His work is widely viewed as the beginning of the “classic period” of the ukiyo-e style. He not only documented the courtesans and actors of the pleasure quarters, but also depicted middle class genre scenes and even street vendors.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 2: 1.2, 1.3; Explorations in Art Grade 3: 5.Studio 27-28; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 4.19, 4.20, 4.Studio 19-20; A Global Pursuit: 7.1, 7.5; Experience Printmaking: 3, 4; Exploring Painting: 9, 11; The Visual Experience: 13.5; Discovering Art History: 2.2, 4.4

Comments