Artists with August Birthdays: Sakai Hōitsu and George Bellows

Monthly artists’ birthdays are a good way to introduce you to a variety of artists I actually adore, while contrasting art from vastly different cultures. I’m not going to call it “interesting,” but it is certainly notable that both of these artists died in January, almost one hundred years apart. They certainly left a lot of beautiful art behind!

|

| Sakai Hōitsu (August 1,1762–January 4,1828, Japan), Cranes. Two-fold screen, ink, colors and gold leaf on paper mounted on wooden frame, 4'9" x 4'9" (143.5 x 143.3 cm). © 2018 Worcester Art Museum. (WAM-152) |

If you ever want to teach a lesson on positive and negative space, this painting would serve as a wonderful example. Its beautiful composition is also a good example of asymmetrical balance. There were so many wonderful schools of painting active through the Edo Period (1615–1868) in Japan, and they were nourished by the isolation of the Tokugawa dictators, who cut outside contact. This caused Japanese artists to look to lauded styles of past periods. One of the most popular styles that persisted through the Edo Period was the yamato-e, one that had come to full bloom during the Heian Period (794–1185).

Yamato-e (“Japanese painting”) originally flourished in the form of scroll painting, particularly in illustration of literature. It is characterized by decorative surface, contrasting patterns, bright color, and the liberal use of gold leaf. During the Edo Period it became a popular style in screen painting. The screen is called a byōbu, and a two-fold screen is a furosaki (or nikyoku) byōbu. The simplicity of this screen is a striking feature in the yamato-e aesthetic in which nature is reduced to shapes, and is typical of the work of Sakai Hōitsu. Although the birds cast no shadows, they do not really seem to float because they are anchored by the stylized stream behind them. The gold leaf background adds to the decorative effect of the screen, composed of 2" (5.1 cm) square sheets of beaten gold leaf.

Sakai was the son of a samurai, the lord of Himeji Castle in Hyōgo Prefecture. You probably know what it looks like:

|

| Himjei Castle, 1333, 1346, and 1601–1609. Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. Photo by Bernard Gagnon. CC BY-SA 3.0. |

Fortunately for us, Sakai shunned the military life and became a painter instead. He was a devoted follower of the Kōrin School of painting, named for its “founder” Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716). This school was sometimes called “Rinpa”: “pa” for school, and “Rin” from Kō(rin). Along with the Tosa and Kanō schools—in both of which Sakai trained—the yamato-e style really flourished up to and through the 1800s. This style is an interesting contrast to the ukiyo-e style with which most Westerners are familiar. Yamato-epainting was favored by the nobility, particularly because of its historical connotations, and was, of course, too expensive for the middle class to afford.

Sakai successfully established a Rinpa school in Edo (Tokyo). He studiously copied many of Ogata’s paintings, often on the back of screens he had painted in his own style. He published two woodblock print albums of Ogata’s work, One Hundred Images of Kōrin and Album of Simplified Seals in the Ogata Style. Talk about hero-worship!

Correlations to Davis programs: Discovering Art History 4E: 4.4; The Visual Experience: 13.5

|

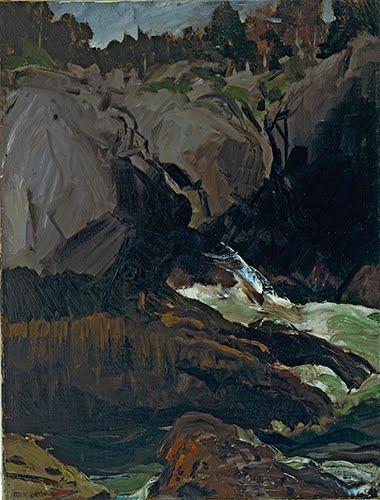

| George Bellows (August 19,1882–January 8, 1925, US), Gorge and Sea, 1911. Oil on canvas. © 2018 Mint Museum, Charlotte, NC. (MIN-12) |

I came to be a big admirer of the so-called Ash Can School artists many, many years ago, first when I discovered Twin Lights, Purple Rocks (1915) by John Sloan (1871–1951) at the Worcester Art Museum. I had never, I guess, thought of the Ash Can artists as colorists, but that painting convinced me they were. What further convinced me was when I saw Vine Clad Shore, Monhegan Island (1913) by George Bellows at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I had never thought of the school as landscape painters, either.

After Vine Clad Shore, I started to note other works by Bellows (and other Ash Can painters) that are infused with an almost Impressionist palette, such as Blue Morning (1909, National Gallery), which is a cityscape. Being a landscape painter, however, I’m so drawn to the landscapes of these artists. I particularly like the broad, fluid brush work of Bellows, no matter what palette he happens to be using. I guess it’s not surprising that they gravitated toward the Impressionist palette, since many of their works—like the Impressionists—lauded everyday city life and were often sketched on the spot.

Unlike the other members of the group of “The Eight,” Bellows was a member of the conservative National Academy of Design in New York that had rejected “The Eight” members’ works and was the impetus for the creation of the “Ash Can School” in 1908. He was elected in 1909, the youngest person ever elected to the academy. Born in Columbus, Ohio, he studied at Ohio State University and then at the New York Art School, where he studied with American Impressionist William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) and Dark Impressionist mentor of the Ash Can painters, Robert Henri (1865–1929).

Works such as Gorge and Sea, above, show the dichotomy of Bellows landscape palettes. It’s dark tonalities and muted colors remind me more of Dark Impressionism than Impressionism. But there is a vitality and an exuberance of paint application that I just really like. Bellows was praised by Academy members for his works that displayed the “American temperament,” whatever that might mean. As much as his cityscapes captured the vitality of city life, so too did his landscape capture the excitement of nature.

Correlations to Davis Programs: A Community Connection: 6.4; Discovering Art History: 4E 15.1

Comments