AAPI Heritage Month 2023: Chan Chao

Photography was a groundbreaking art form when it was first introduced. Quite soon after its development, numerous Western photographers explored photography for documentary and journalistic purposes. That helped lay the groundwork for the burgeoning field of documentary photography, which flourishes to the present day. Documentary photography has become a respected discipline practiced by artists around the world. Photographer, art educator, and human rights activist Chan Chao has used his photography to document the little-reported struggle for democracy in Myanmar (Burma).

|

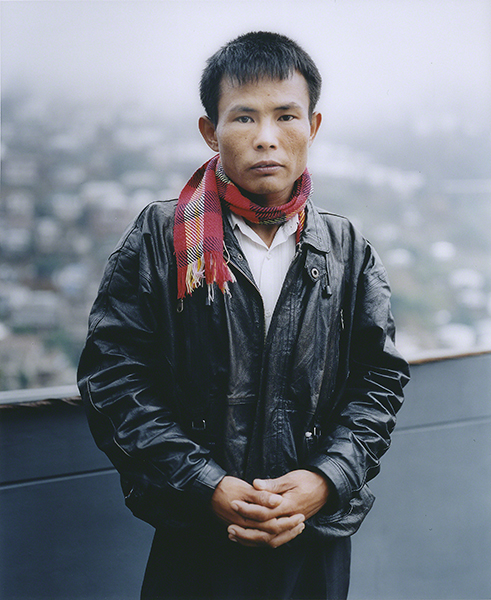

| Chan Chao (U.S., born 1966 in Myanmar), Soy Myint, 1997. C-print laminated to plexiglass, 35" x 30 ¼" (88.9 x 76.8 cm). Smithsonian Institution, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC. © 2023 Chan Chao. (SI-32) |

Portraits from Chao’s portfolio/book Burma: Something Went Wrong (2000) emphasize each subject as an engaging individual and a person of restrained dignity. These men and women were part of a resistance movement, but the sitters share an amazing sense of calm and reserve. Soy Myint, his hands clasped peacefully in front of him, his forthright gaze connecting with the viewer, is taken from an intimate distance. He is placed in the middle of the frame, surrounded by the soft-focus hillside backdrop. Such portraits do not resemble those of an armed resistance movement, but rather simple representatives of rural life.

Chao often suggested the sitter hold a familiar object while being photographed, a way for them to be at ease as they posed. In Soy Myint, the sitter's bright, joyously colored scarf acts as an anchor for this meditative portrait. Small personal details in Chao's work reflect his ongoing commitment to underscoring human rights and the dignity of every human being. At the same time, the series of portraits cannot help but emit the sense of a people who may be longing for the simpler pleasures of everyday life rather than armed resistance.

Photography appeared in Burma soon after its development in Europe in the 1830s and 1840s. The earliest photography in Burma was naturally introduced by British invaders. Many studios were set up in Burma by colonial photographers, mostly in the interest of creating colorful and “quaint” views of the country and people for postcards, as well as a foreign interest in the “exotic.”

In the first decade of the 1900s, colonial-era photography studios had expanded to provide developing services, film, and equipment for amateur photographers, most certainly not Burmese, but many of them Burma-born Europeans. The cost of colonial-era photography meant that all photography firms were foreign (mostly British) owned. There is little to no evidence of Burmese natives being amateur photographers, although by 1900 the foreign-owned firms were listing native Burmese as employees.

D. A. Ahuja (ca. 1865–ca. 1939), born in Burma of Indian descent (as the British had forced Burma to be a province of “British India”), was a photographer with his own studio starting in the first decade of the 1900s. Ahuja is known to have bought out many foreign photography firms by the second decade of the 1900s. He ran them with indigenous employees.

Burmese photography expanded steadily through the 1900s. After Burma declared independence from Britain in 1948, Burmese photographers established the Rangoon Photographic Society in 1950, which soon changed its name to the Burma Photographic Society. The group aspired to improve the technical knowledge and experience of Burmese photographers. The 1950s also saw a rise in the number of educated amateur photographers.

Since a 1962 military coup overthrew a democratic government in Burma, Burmese photographers have been instrumental in documenting the status of Burmese society, as well as the numerous crimes committed by the military junta. Contemporary Burmese photographers also continue the tradition of portraiture of all aspects of Burmese society in order to bring a sense of continuity in their culture, despite the oppression of the military.

Chao was born in Kalemyo, Burma, leaving for the U.S. with his family when he was 12 years old. He studied photography at the University of Maryland, College Park, under urban documentary photographer John Gossage (born 1946). He currently teaches at the Corcoran School of the Arts & Design at The George Washington University and has published three photography books.

In 1996, Chao decided to rediscover and reconnect with his homeland, which was called Myanmar by the military junta starting in 1989; a name that is the written version for the country in the Burmese language. Chao's request for a visa was denied, so he snuck into Myanmar from the Thai border. In his visits over the next two years (1997 and 1998), he produced more than 150 portraits of students and young rebels in border camps with India and Thailand, from which they launched attacks on the Burmese government troops, hoping to restore democracy.

Unlike other documentary photographers who prefer to shoot dramatic images of resistance, Chao chose to produce portraits that showed the variety of people involved in rebellion and their humble, yet dignified lives. He hoped not only to raise awareness about the struggle in Myanmar, but also to explore his conviction that understanding the struggle helps on the road to uniting all people of conscience.

Correlations to Davis programs: Experience Art: 2.1 Studio Investigations and Studio Experience; A Community Connection 2E: 7.2; The Visual Experience 4E: 9.1; Focus on Photography 2E: Chapter 5, Chapter 6

Comments