Art of Libraries

April 20th through 27th is National Library Week. We all like libraries. Like museums, they have such a special ambience. In order to celebrate that in an art historical manner, let’s look at some interesting works of art that deal with the subject.

|

| Pietro Longhi (1701–1785, Italy), Visit to a Library, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas, 23 ¼" x 17 3/8" (59 x 44 cm). © 2020 Worcester Art Museum. (WAM-90) |

Pietro Longhi's depiction of elegantly dressed wealthy people is worthy of a French Rococo painting. The glittering elite are contrasted against a neutral background. Focusing on rich people with no obvious interest in reading, touring a library is an ironic artistic statement. It reflects the common dissatisfaction with the upper classes, a sentiment that, in some countries, built toward the democratic revolutions in the late 1700s.

Longhi's genre scenes typically feature an elegantly dressed woman as the central focus. She is dressed in the height of Rococo French fashion. The characters are inevitably generalized idealizations of fashionable young people with more emphasis on the elegance of the idle rich rather than specific individuals.

While the paintings of the French Rococo celebrate the mindless frivolity of the ruling class, many artists of the 1700s, particularly in Britain and Italy, enjoyed using the visual language of the Rococo in subjects that focused on everyday life. This was particularly effective in works that pointed out the artificiality of social conventions among the wealthy, a reflection of Enlightenment ideals.

Italy had no central court that guided the development of a distinctive Italian school of painting from Renaissance times on. Painting styles still varied from region to region oriented around major cities: Florence, Rome, and Venice.

Longhi, based in Venice, originally trained as a history painter, but later studied under the genre painter Giovanni Maria Crespi (1665–1747). His genre subjects bear the influence of the French Rococo artist Nicolas Lancret (1690–1743), but they also include elements of Dutch Baroque genre painting, a large collection of which existed in Venice at the time. He devoted himself to scenes of everyday life and produced some portraits and landscapes.

|

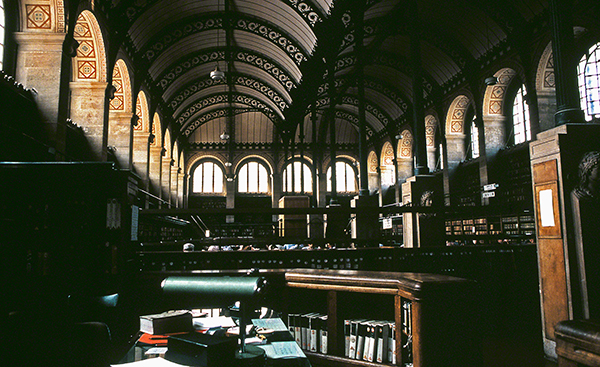

| Henri Labrouste (1801–1875 France), Bibliothèque de Sainte-Geneviève, Paris, 1843–1850. Image © 2020 Thomas A. Heinz. (TAH-116) |

Henri Labrouste’s design for the Library of Sainte-Geneviève was probably the first design in which a library was perceived as a “temple of knowledge” for public use rather than just a storehouse of books available only to scholars. His design was also revolutionary, being one of the first buildings to explore the structural possibilities of cast iron. The main reading room consists of sixteen slender cast-iron columns supporting a double barrel vault with cast-iron arches instead of masonry. The result is a light-filled room with the double barrel vault complementing the arcade of arched windows that ring the entire building.

Labrouste’s design was a parting shot at the domination of Neoclassicism, a doctrinaire and sterile style that had evolved during the late 1700s after the discovery of the ruins of ancient Pompeii. By the 1820s, parallel to the Romanticism movement in painting, architects began looking beyond the styles of ancient Greek and Roman architecture as models for buildings. What resulted was a century in which every past Western architecture style, and some non-Western, was explored for design and decorative possibilities in European architecture. This library falls under the loose revival style called Renaissance Revival.

Born in Paris, Labrouste studied architecture at the School of Fine Arts there. He won the Prix de Rome and studied in Italy for six years. There, he was more impressed by the rational adaptation of classicism in Renaissance architecture, rather than a strict interpretation of the ancient styles. The Library of Sainte-Geneviève shows the influence of many Italian Renaissance buildings, including the Michelozzo’s Medici Palace in Florence, Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence, and the Tempio Malatesta by Alberti in Rimini, among others.

|

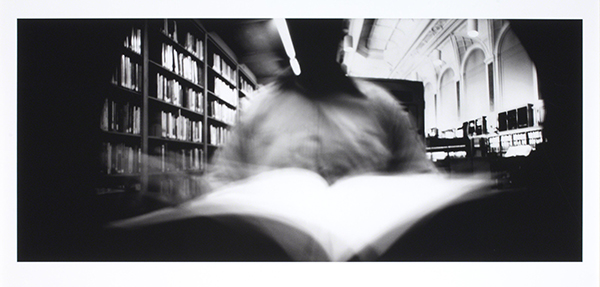

| Ann Hamilton (born 1956, U.S.), Free Library of Philadelphia, from the series Face to Face, 2006. Digital print from pinhole negative, 7 5/8" x 18" (19.5 x 45.6 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2020 Ann Hamilton. (PMA-3058) |

Ann Hamilton’s pinhole work was a dramatic shift from her installations, which were totally immersive. The fact that she devised a pinhole camera inserted in her mouth, with her closed mouth as the aperture, switched the idea of “surround” to her mouth. The pinhole camera contains photo-sensitive support such as treated paper, which records the image when the aperture (Hamilton’s mouth) opens.

Intrigued with the idea of capturing people unaware—while involved in everyday actions—creates an intimate portrait that becomes an immersive experience into the activity. There is a duality of the idea of unselfconsciousness for both artist and subject: the artist in having to open her mouth to take the photo and the subject being caught without much warning.

The mouth/aperture acts as a frame for this subject who is caught flipping through a book. Hamilton has likened the shape of the mouth’s opening to the shape of an eye, with the “sitter” acting as a pupil. Hamilton’s work presents the ironic aspect of her pinhole photographs wherein the source of speech (the mouth) in these works functions as the source of sight (the eye).

The theory behind the pinhole camera has been around since at least the 400s BCE in China. Pinhole imagery was discussed by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE), and in the 900s CE by the Iraqi mathematician Ibn al-Haytham (ca. 965–ca. 1040). Early pinhole cameras were small and made from any hollow, light-safe object with a small hole. For the next several hundred years, pinhole imaging was used primarily for close scientific study.

During the 1500s, the camera obscura was developed in Western Europe. It enlarged the concept of the pinhole camera to room-sized, with an aperture fitted with a lens. The first pinhole camera is thought to have been perfected by David Brewster (1781–1868), a Scottish physicist, around 1855. During the 1880s, photographers of "art photography" or Pictorialist inclination preferred the pinhole camera. Without a lens, the lack of depth of field created indistinct (fuzzy) edges and background images, imitating the painterly nature of Impressionist painting.

Interest in pinhole photography revived during the late 1900s. This time, however, it went beyond stylistic or scientific interest, and was impacted by philosophical or sociological concerns.

Hamilton is an artist renowned for her installations and performances that incorporate the mundane activities of life, in both visual and auditory terms. She documents these activities in print, object, and video editions as an archive of the processes that comprise her interest in the structure of language and other modes of communication. Starting in 2001, her ongoing series Face to Face explores unguarded moments of everyday activities caught by a pinhole camera.

Hamilton was born in Lima, Ohio, and received her BFA in textile design at the University of Kansas and an MFA in sculpture from Yale University. After teaching at the University of California, Santa Barbara (1985–1991), she has taught at Ohio State University since 2001.

Comments