An Ode to "Swiss"

I just returned from a week in Switzerland to visit family. Walking through their churches—stripped of all sculpture, painting, and Biblical stained glass because of the Reformation’s frowning on “idolatry”—I mused that few people realize that the “Renaissance” happened in countries other than Italy, France, Spain, Germany, and Flanders. Also, I think most people do not realize how much Swiss artists have been an intricate part of art history right up to the present day.

|

| Josef Gössler (active 1540–1585), Window with an allegory of Justice, with the arms of Anthony Wyss, 1570, for a church in Bern. Stained and painted glass, leaded, 13 3/4" x 12" (34.9 x 30.5 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3518) |

As part of the stylistic term “Northern Renaissance,” the Swiss version was a very short-lived period. It was fueled by the wealth of booty taken from the Flemish ruler Duke Charles the Bold (died 1477), who tried to establish a Flemish kingdom from Flanders through Alsace to Italy through Switzerland, but the Swiss defeated him in Murten (Morat) and then Nancy. The brief explosion of money available for art commissions was extinguished in the Protestant Reformation that evolved in Switzerland around 1523–1525. Most artists assisted in the destruction of their own artworks that depicted Biblical scenes.

Bern was an active center of painting and also stained glass works. Most painters supplemented their incomes by doing stained glass. Many Swiss artists of the period naturally visited Rome and other Italian centers of art to learn the latest style. After the Reformation, allegorical, classical and mythological scenes were popular, as was, particularly, the celebration of lineage through windows donated to churches by wealthy families. This window, dedicated to a wealthy burger of Bern, displays the peculiar influences that dominated Swiss art through the 1600s: a combination of the Danube School and Italian Renaissance classical motifs.

Here are some other Swiss artists you may not know:

|

| Jost Amman (1539–1591), Head of a Bearded Man, 1572. Ink and white wash on blue prepared paper, 6 1/8" x 4 1/2" (15.6 x 11.5 cm). © National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. (NGA-P1034) |

Amman, born in Zürich, was a prolific draughtsperson and printmaker. Unlike Gössler, he reflects more of the Danube School (German) influence in late Renaissance art, and he carries on the tradition of the great German Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). His work is quite similar to the German artist Albrecht Altdorfer (1480–1538). Works such as this allude to the Swiss penchant for mercenary military service.

|

| Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789), Portrait of François Tronchin, 1757. Pastel on parchment, 15" x 18 1/4" (38 x 46.3 cm). © Cleveland Museum of Art. (CL-45) |

Although Liotard, a Genevois, studied and worked in Paris, he produced most of his portraits of the influential people of Geneva. Tronchin was a lawyer, writer, and art collector in Geneva. Liotard ably incorporates the 1700s Rococo style. While stressing a reserved elegance, Liotard endows the portrait with a dignity that alludes to his scholarly accomplishments. His beautiful pastel portraits measure up to the ablest French Rococo portraitists.

|

| Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807), Portrait of Helena Mecinska, 1790s. Oil on canvas. Private Collection, Photo © Davis Art Images. (8S-6487) |

Born in Chur in Graubünden, like most women artists of her time, Kauffmann was trained by her artist father. She moved to Rome where her portraits became fashionable among English visitors. She subsequently moved to England for several years. Returning to Italy, she married a Venetian artist, and was buried in Rome with great pomp. Her portraits reflect the Neoclassicism of late 1700s and early 1800s painting. This portrait of a noble Polish woman in Rome is very similar to those of another prominent woman artist of the period, the French Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755–1842).

|

| Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (1859–1923), Poster for Compagnie Française des Chocolats and des Thés, 1895. Color lithograph on paper, 30.7 x 23.2 cm (12 1/16" x 9 1/8"). © Cleveland Museum of Art. (CL-951) |

Starting in the late 1800s, Switzerland became a major influence in graphic design, particularly in poster art. Born in Lausanne, like many Swiss artists of the period, Steinlen migrated to Paris. His lithographs betray the influence of the French Post Impressionists, particularly the group called the Nabi, who reduced compositions to colored shapes and areas of contrasting patterns. Although he began as a painter, his major influence is in poster design.

|

| Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), Object, 1936. Fur-covered cup, saucer and spoon, saucer width: 9 5/16" (23.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2013 Estate of Meret Oppenheim / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (MOMA-S0108opars) |

Born in Germany of a Swiss mother from Delémont, Oppenheim first exhibited the fur tea cup in Switzerland in 1936. She studied in Paris under such avant-garde surrealists as Jean Arp (1886–1966, born France), Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966, Switzerland), and André Breton (1896-1966, France). She exhibited in Surrealist exhibitions until 1960. Object takes an everyday piece and subjects it to the subconscious combination of irrational elements (such as the Chinese gazelle fur on a tea cup).

|

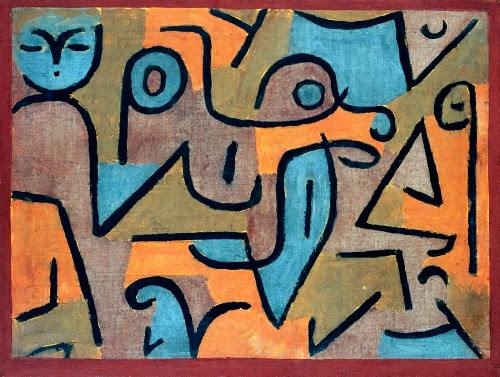

| Paul Klee (1879–1940), Young Moe, 1938. Gouache on newspaper mounted on burlap, 20 7/8" x 27 7/8" (53.0 x 70.8 cm). The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. © 2013 Estate of Paul Klee / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (PC-197klars) |

Although associated with Germany because of his tenure at the Bauhaus, Klee was born and died in the Canton of Bern. He was a friend of my grandfather’s sister Helena. His personal form of fantasy had connections to Surrealism, but also the fragmentation of Cubism. This work combines both strains of early modernism.

|

| Le Corbusier (Charles Édouard Jeanneret, 1887–1965), Notre-Dame-du-Haut, 1950–1954, Near Ronchamps, France. Photo © 2013 Davis Art Images. (8S-15093) |

Born in La Chaux de Fonds, Le Corbusier became a French citizen in 1930. He is one of the pioneers of the International Style in architecture, in both the organic and geometric strains. This pilgrimage chapel is a perfect example of the organic strain emphasis on groupings of masses as opposed to strict geometry. Both strains avoid any undue surface ornament or allusions to classical architecture.

|

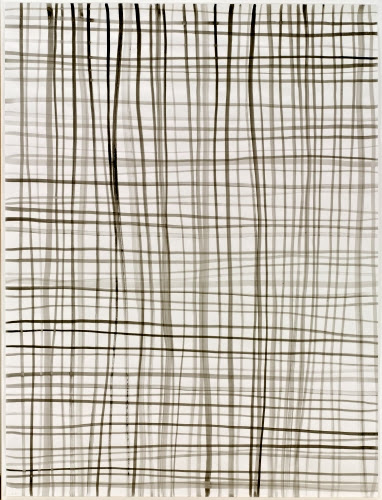

| Silvia Bächli (born 1956), Lines 39, 2007. Ink on paper, 78 1/4" x 59" (198.8 x 149.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2013 Silvia Bächli. (MOMA-P4358) |

Basel-based artist Silvia Bächli is famous for her sparse, intricate drawings. Her work documents detailed aspects of the physical world. She believes that the drawing exists beyond the edge of the paper, so that her works take on the nature of close-up objects. Lines 39 could represent the weave of a textile, or merely Bächli’s interpretation of that. She currently is also working with photography.

Comments