The Intriguing Peter Blume

One super-prime example of why it is often unwise to stick with labels for artists’ styles is the term “Painters of the American Scene,” or “American Scene Painting.” This term is so hugely umbrella-like that it makes certain art historians dizzy (not really). In many texts, studies of the American Scene include Regionalism; Social Realism; Magic Realism (a distant cousin to Surrealism); and plain, unadulterated personal forms of realism.

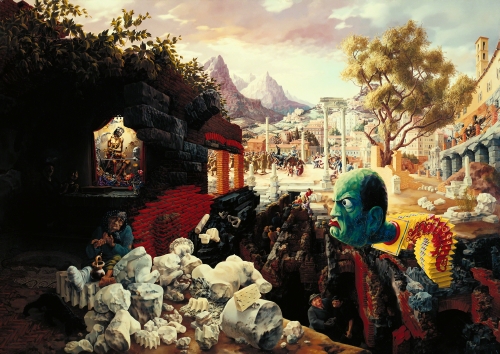

If I had to choose one of those designations to describe the paintings of Peter Blume, Magic Realism comes the closest, but it so does not sum up the breadth of expression in his body of work.

|

| Peter Blume (1906–1992, US, born Belarus), The Shrine, 1950. Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard and panel, 18" x 22 3/4" (45.7 x 57.8 cm). Brooklyn Museum. © 2015 Estate of Peter Blume / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (BMA-5050Abuvg) |

Realism blossomed in American art in the isolationist and ethnocentric aftermath of World War I (1914–1918), particularly during the era of the Great Depression (1929–1939). It was during this time in the 1930s that Blume’s mature work evolved. However, Blume’s form of realism was far from that of Edward Hopper or Thomas Hart Benton. Blume emigrated from Russia with his family at the age of five. He studied art in New York and had his own studio by the age of 18. His historical artistic interests lay in Renaissance painting from both Italy and northern Europe, although, in his obsessive detail of objects from the physical world, his paintings lean closer to the passionate observed realism of Flanders and Germany during the Renaissance. He trained under brothers Raphael (1899–1987) and Isaac Soyer (1902–1981), Russian immigrant artists who were avid realist painters, whose depictions of everyday American life during the Depression could appropriately be called Social Realism.

In 1932 Blume won a Guggenheim Fellowship and spent a year in Italy, which inspired his first major sensation of a painting in 1934: The Eternal City. Inspired while standing in the Roman forum, the jack-in-the-box menacing head of the fascist dictator Mussolini is a portent of rapidly approaching World War II (1939–1945). On the left side of this painting is the Man of Sorrows, Jesus during his ordeal before crucifixion, a running theme in Blume’s work.

|

| Peter Blume, The Eternal City, 1934–1937 (dated 1937). Oil on composition board, 34" x 47 7/8" (86.4 x 121.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Peter Blume Estate / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (MOMA-P076buvg) |

Throughout his career, Blume maintained his own personal vision in his work, even with the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism during the 1950s. The Shrine is one of several versions of the Man of Sorrows theme, one that could easily come out of private devotional images from Spanish Renaissance or Baroque art, particularly in the placement of the figure on what looks like a draped altar. In both of these paintings one sees elements of Surrealism, although Blume himself denounced the movement in print because of its theories about unconscious creation and its associations with sensual themes from the subconscious. Many of Blume’s paintings included everyday objects that he observed in his travels around the Northeast. Many of Blume’s post-war paintings reflected the sorrow at its destruction, yet the hope for rebuilding. In The Shrine, Blume’s Surrealist experiment comes the closest to any examination of the psychology of suffering in the badly scarred and emaciated body of Christ. At the same time, it reflects a sense of faith in the tiny pilgrim badges adorning his loincloth—symbols of the faithful, a tradition dating back to the pilgrimages in Europe during the Middle Ages (ca. 1000–1400).

After leaving New York, Blume and his wife moved to Connecticut and grew vegetables. He produced many landscapes and still life paintings. While one is tempted, in this pre-war landscape, to read a contrast between the poppies symbolizing life and hope and the stark, craggy rocks as the coming devastation of war, I see it more as evidence of Blume’s uncanny ability to depict nature in minute detail, almost like Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo da Vinci. Stones recur in many of his works.

|

| Peter Blume, Landscape with Poppies, 1939. Oil on canvas, 18" x 25 1/8" (45.7 x 63.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2015 Estate of Peter Blume / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (MOMA-P0702buvg) |

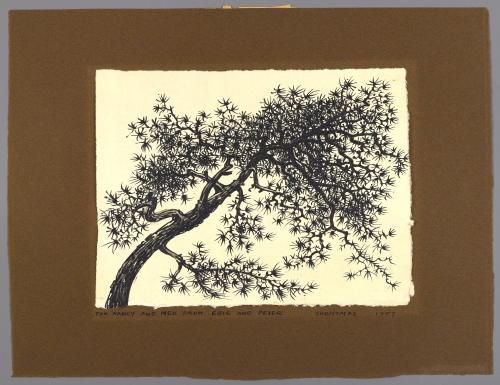

Blume did copious studies of figures and elements of nature for all of his paintings. This lovely little pine tree branch may have been a study for a painting, but is lovely on its own. It has an almost Japanese quality in its craggy branches and asymmetrical composition. It may have been inspired by something he saw during a trip to the Pacific in the mid-1950s.

|

| Peter Blume, Untitled (Branch of Tree), 1957. India ink on Japanese paper, 8 1/4" x 11" (21 x 27.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum. © 2015 Estate of Peter Blume / Licensed by VAGA, New York. (BMA-5051buvg) |

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 3: 3.17-18 studio; Explorations in Art Grade 4: 6.31, 6.34; Explorations in Art Grade 5: 6.34, 6.35, 6.33-34 studio; A Personal Journey: 1.3, 7.4; A Community Connection: 6.2, 7.4; Experience Painting: 6; Exploring Painting: 10; Exploring Visual Design: 1, 10; The Visual Experience: 9.3; Discovering Art History: 15.3

Comments