American Artist Supports American Art: Carroll Beckwith

I guess it doesn’t need to be said, that, in the history of art, there are many artists who just don’t get massive exposure. Although they might often be lauded in their day, their works don’t find their way into “official” art history surveys. Well, I’m here to correct that on a weekly basis.

I really like finding artists who are not household names, but whose works are beautiful and compelling for the period in which they were executed. Such is J. Carroll Beckwith, or Carroll Beckwith as he wished to be called. He epitomizes an artist who was working as an agent for art on the verge of modernism, but, whose work—although on the cusp—never quite got there. And there’s nothing bad about that, because his work is Beautiful! And, he was a major advocate for encouraging an indigenous American school of art.

|

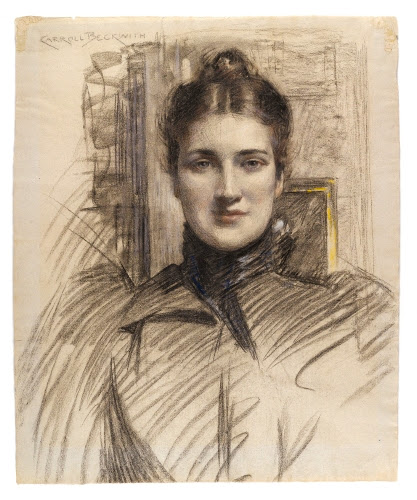

| J. Carroll Beckwith (1852–1917, United States), Portrait of Minnie Clark, 1890s. Charcoal and colored pencil or pastel on blue-grey laid paper, 10 ¼" x 6 ¾" (26 x 17.2 cm). © Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-3439) |

American art really came into a strongly individual nature in the late 1800s. Many artists, like Beckwith, studied in Europe, but often what they brought back was a personal style influenced, though not dominated by, what was going on in Europe, namely Impressionism. Although many art historians are tempted to classify Beckwith as an Impressionist, I find his work to be a fascinating combination of that style with the dogged interest in realism that characterized American art during the 1800s.

What interests me the most about Beckwith—other than his beautiful portraits—is the fact the he was so supportive of struggling American artists during his lifetime. A member of the Artists Fund Society in New York, he worked for the benefit to needy artists and their families. He helped raise money for a new building for the Arts Student League (where he had studied), which also housed the Society of American Artists, the Architectural League, and the Art Guild. The Arts Students League is still housed there in what was then called the American Fine Arts Society.

|

| Mary Cassatt (1844–1926, United States), Woman Arranging Her Veil, ca. 1890. Pastel, 25 ½" x 21 ½" (64.8 x 54.6 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-622) |

Although Beckwith studied abroad, notably with American John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), his work remained solidly realistic. Beckwith’s portraits always insist on the solidity of the form, while displaying an awareness of the Sargent / French Impressionist emphasis on light and broken form. Compare his solidly modeled form with that of Cassatt. Her work is filled with light and the Impressionist preference for depicting shadow in pure colors rather than black. Interestingly, this drawing by Cassatt displays the same gestural technique as in the Beckwith.

|

| Charles Dana Gibson (1867–1944, United States), Young Woman, ca. 1900. Ink on paper, 10" x 12" (25.4 x 30.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY. (BMA-3196) |

Minnie Clark was a favorite model of Beckwith’s, and is thought to have been one of the inspirations behind Gibson’s “Gibson Girl” of the 1890s to 1910s. The Gibson Girl was an odd assertion of the modern American young woman with bizarre misogynistic aspects, such as this lovelorn beauty with “arrows” lodged in her heart. The Gibson Girl, though, was an affirmation of the coming emancipation of modern American women, which started during World War I (1914–1918), albeit as a “sex symbol.” One can see this idealization in the portrait of Minnie Clark. What a contrast between Cassatt’s work and that of Beckwith and Gibson!

Studio Activity: Draw a Face with values. Set up a light source to show highlights and shadows either in a self-portrait or portrait. Using charcoal on paper, record the darkest values first. Using white chalk or white color pencil, introduce sharp changes in value. Use a blender to blend the various values from light to dark.

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 3 1.1, 1.2; Explorations in Art 4 2.7; Explorations in Art 5 1.1, 1.2; Explorations in Art 6 1.2; A Community Connection 2.2; The Visual Experience 9.2

Comments