An African Photographer: Seydou Keïta

In looking at the history of art, I always try to appreciate art that is under-appreciated. Photography has been accepted as an art form since the early 1900s, although is it rarely studied outside of Western Europe or America in western art history. But, let’s think of art forms, long under-accepted in the West, in Africa.

We tend to think of masks, textiles, and ancestor figures when “African Art” is brought up. The photographer Seydou Keïta is a brilliant example of the richness of African art in the post-colonial period. His native Mali achieved independence from the French in 1960. Keïta’s portraits document Mali’s transition from a cosmopolitan French colony to an independent country. Keïta’s art also shows how art enhances the dignity of every human being.

|

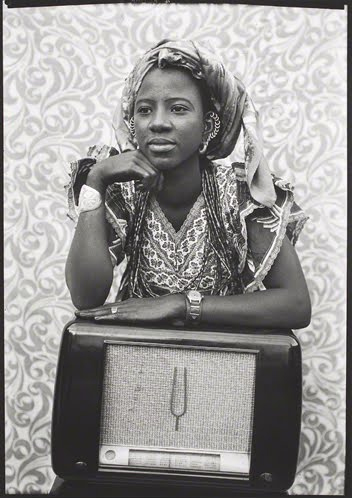

| Seydou Keïta (1923–2001, Mali), Woman with a Radio, 1956–1957, printed 2002. Gelatin silver print, 17 11/16" x 15 ½" (44.9 x 39.4 cm). Photo © Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with funds contributed by David and Jaimie Field. (PMA-3356) |

By the turn of the twentieth century, photography was well on its way to being considered a form of “fine art.” Photography served as an important tool in the 1950s and 1960s for documenting performance art, installations, and happenings. Some photographers chose to continue to document society and the rapid changes happening to it. The 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition (curated by Edward Steichen) of photographs emphasized birth, love, and joy, and also touches of war, privation, illness, and death. His intention was to prove visually the universality of human experience and photography's role in its documentation. The exhibition proved that one of the most important impacts of photography on society was its ability to document the state of humankind.

Keïta eloquently portrayed society of the Mali capital Bamako during a period of transition from a “colony” to the modern African nation. Initially trained as a carpenter, Keïta began pursuing photography after his uncle gave him a Kodak Brownie camera in 1935. He mastered the art of composing printing and subsequently bought a large format camera. In 1948 he opened his own studio in Bamako and quickly built up a successful business of portraiture. His subject matter became primarily portraiture of the burgeoning middle-class and successful business class of the increasingly affluent Mali society. He balanced a strict sense of formality with an intimacy evinced by the props and backdrops (most often native textiles) he had available in his studio. The radio is seen in several portraits of different persons.

After a period of photographing for the Mali government, Keïta retired in 1977. The discovery of his work in the 1980s by French gallery owners led to world-wide recognition in the 1990s. His first exhibit in the US was 1991. His work represents the founding stage of African modernization as experienced in a lively, thriving city (Bamako). By the 1990s he had an archive of over 10,000 negatives. His emphasis on light, subject and framing establishes Keïta among the masters of the 20th century genre of photography.

Correlations to Davis Programs: Focus on Photography, The Visual Experience: 9.5, SchoolArts Magazine Looking & Learning: October 2010 (Commemoration), January 2011 (Place), February 2011 (Time)

Comments