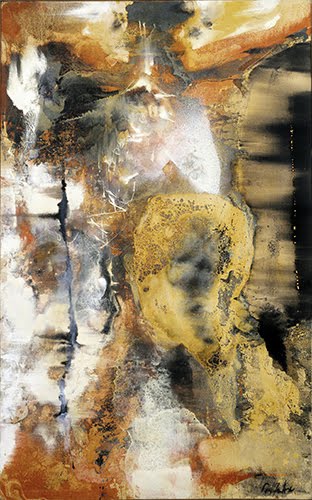

Abstract Expressionist Paul Jenkins

Some art historians, when discussing an artist’s work, will say “oh, but he’s (or she’s) a brilliant colorist!” I’ve never really known when to use that phrase with the proper cachet, but I would be wallowing in understatement if I used it in any description of the work of Paul Jenkins. This artist’s work is simply stunning.

Now, I’m a big fan of Helen Frankenthaler’s (1928–2011) stain paintings because they are brilliant and quite often evoke landscape to me. But, Jenkins’ works starting in the late 1950s absolutely knock my socks off with their high-intensity color. I’m a big sucker for color, as you know, and Jenkins’ paintings are a celebration of pure color. I think the only other Abstract Expressionists whose work excites me on this front are Mark Rothko (1903–1970)—before he started experimenting with black and brown—and Grace Hartigan (1922–2008).

|

| Paul Jenkins (1923–2012, US), Phenomena Voyager, 1972. Watercolor on paper, 3' 6" x 2' 6" (106.5 x 76.2 cm). Smithsonian Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC. © 2019 Paul Jenkins/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (SI-489jkars) |

One of the main tenets of Abstract Expressionism was the artist expressing the inner self, with the finished painting a record of the process of that search. Most of the Abstract Expressionists were in sync with that philosophy and with the Jungian idea of the disconnect from the body while producing art. Jenkins is an interesting personality in the world of Abstract Expressionism. Like Mark Tobey (1890–1976), the fellow New York School artist he befriended, Jenkins’ work was inspired by more than Jungian philosophy and the Surrealist-inspired emphasis on subconscious creation. The reliance on spontaneity of Zen Buddhist meditation, the theories about constant internal change of I Ching philosophy, and the reflective abstract imagery in Symbolist painters such as Odilon Redon (1840–1916) had major impact on Jenkins work since early in his career.

From early on, as well, Jenkins experimented with different methods for spreading his paint into the jewel-like color and semi-transparent veils of paint that are his signature style. He rarely, if ever, used a brush to spread paint. Most often, he used knife-related tools, including his favorite ivory-handled knife. Fascinated with the stain paintings of Frankenthaler and Morris Louis (1912–1962), Jenkins devised his own method of pooling, rolling, and flowing paint on the canvas with a control that allowed the pure intensity of the colors to shine through. He often dripped thin lines of white paint to set off colors.

As early as 1958, he called himself an “abstract phenomenist,” indicating that his work reflected god inside of him. From that year on, he titled most of his works Phenomena, searching for ways to express ideas rather than forms that people would subsequently search for in his works. His use of more luminous colors began in the early 1960s. When looking back at his work, one marvels how he created luminous compositions in a variety of pigments (oil, acrylic, watercolor) as well as lithography.

Jenkins was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and spent some of his childhood in Youngstown, Ohio. Although he met both Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) and Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) as a young person, they did not impact his art. Wright even suggested that Jenkins take up farming. After service in World War II (1939–1945), he moved to New York in 1948 and studied at the Art Students League. In New York, during that germinal moment in American modernism history, Jenkins befriended Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), thrilled by the dynamism of his painting, and Mark Rothko (1903–1970), whose brilliant colors appealed to him. With all of the influences that Jenkins encountered, he developed a distinct abstract style that has stood the test of time in luminosity and brilliant appreciation of pure color.

I have to admit, I prefer his palette after 1958 to this early one, though the way he spread the oil paint is very exciting.

|

| Paul Jenkins, The Archer, 1955. Oil on canvas, 4' 3" x 2' 8" (129.9 x 81 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. © 2019 Paul Jenkins/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (AK-439jkars) |

The work below is a simply stunning piece, if not only for the brilliant color (especially my favorite, the violets), but for the scale. Can you imagine controlling the free-flowing on paint such a large canvas?!

|

| Paul Jenkins, Phenomena Anvil Compass, 1981–1983. Acrylic on canvas, 6' 3" x 12' 6" (190.5 x 381 cm). Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio. © 2019 Paul Jenkins/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (BIAA-559jkars) |

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 4: 6.35; Explorations in Art 1E Grade 4: 6.7; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 6: 5.25; Explorations in Art 1E Grade 6: 5.1; Exploring Painting 3E: Chapter 5 studio experience; Discovering Art History: 4.3 17.1

Comments