Memorial Day: Mathew Brady

I think it’s appropriate—with so many new veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars—to salute American soldiers this Memorial Day. My daddy was a veteran of the army in World War II (Pacific) and it never fails to amaze me how so many veterans go through harrowing experiences in war and are expected to come home to resume normal lives.

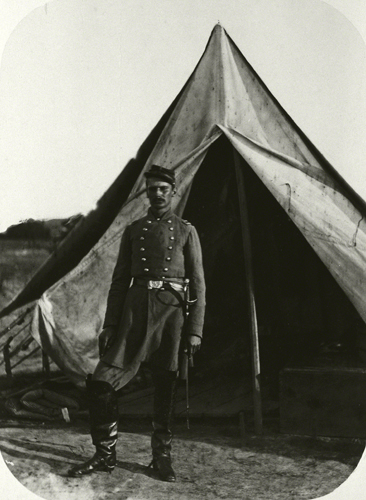

Unfortunately, since Vietnam, it has become harder for veterans to achieve this. I would like to reflect on one of the most divisive, destructive, and deadly wars in US history—the Civil War (1861–1865) —and the effect it had on art. It is really unfortunate that there are so many soldiers who have become anonymous. This photograph of an unknown soldier sort of sums up my feelings about war and the waste of lives. But this portrait also points to the pride in our military and their dedication to defending this country.

|

| Mathew Brady (1823–1896, United States) or assistant, Soldier Before His Tent, 1862. Albumen print, 7 7/8" x 5 7/8" (20 x 15 cm). Private collection. (8S-20479) |

The Civil War was the first war documented by photography. Unfortunately, it was the war that resulted in many advances in the art form. The importance of photography from that period on was its ability to document facts without any emotional or subjective interpretation. Mathew Brady was one of the earliest and most prominent of the early photographic portraitists in the US. But it was his Civil War photographs that made him one of the most important photographers in the early decades of photography.

Brady was the son of poor Irish immigrants who arrived in New York in the mid-1830s. In the 1840s he was introduced to the artist Samuel F.B. Morse (1791–1872, inventor of the telegraph), who had introduced the Daguerreotype process to the United States. By 1844, Brady had established a portrait studio, and by the 1850s, he had fashionable portrait studios in Washington, DC and New York. He was a friend to politicians and other members of elite society. He had an unerring sense of what the public wanted, and set high standards of quality.

Sensing that photography was destined for more than just being a commercial enterprise, he closed his portrait studios and set out to document the war in 1861. He had sturdy wagons constructed for carrying the glass plates, chemicals, and other equipment. During the war, Brady risked his life to take many of the photographs himself, although he still relied on numerous assistants, many of whom never got credit for their work. This straight portrait of a soldier is typical of his aesthetic for the venture: he was recording historical fact. This iconic portrait of an unknown soldier is emblematic of the power of photography even at this early stage in its development.

Comments