It's That Time Again

By that, I don’t mean “it’s November” or “it’s autumn.” I suspect that I’m not the only one who is tired of political ads with mean-spirited denunciations of opponents. Probably, though, each quadrennial election we endure is no worse than any that have gone before, since the first presidential election of 1788–1789.

Well, maybe that one was more civilized because George Washington was in it. Voting and elections have not escaped the realm of subject matter in art. Here are three examples from radically different time periods, and, times that were contentious as they are in the present day.

|

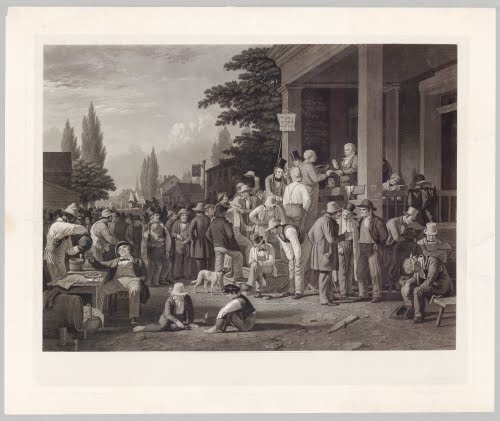

| John Sartain (etcher, 1808–1897, born Britain), after George Caleb Bingham (1811–1879, US), The County Election, 1854. Etching, engraving and mezzotint on paper, image: 11 7/8" x 18" (30.2 x 45.9 cm). © American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA. (AAS-126) |

I’m not certain why John Sartain engraved this George Caleb Bingham painting in 1854. It may have been because the congressional election of 1854 was fraught with conflict in the Midwest over the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in August of that year, which did away with the Missouri Compromise on slavery of 1820. That allowed Kansas and Nebraska territories to choose to be either slave or free, and led to violent civil conflict in Kansas ultimately called Bleeding Kansas. I’m sure there were many elections fraught with heated rhetoric as the country headed toward the Civil War (1860–1865).

The painting from which this is taken was painted by Bingham in 1852 to commemorate the congressional elections of 1850, in which Bingham unsuccessfully ran for Congress. The opponent, E.D. Sappington, apparently bought votes with liquor. This is Bingham’s wry comment on the foibles of a young American democracy, where, obviously only the men voted (after taking an oath on a Bible, which I did not know). Bingham depicted himself in the center on the courthouse steps probably sketching, ignoring the tomfoolery around him.

Bingham was the first significant painter of genre subjects in American art. Born in Virginia, he was raised in Missouri, and had a solid respect for the hardy frontier people who helped settle the West. His paintings, meant for east coast audiences, elevated frontier people into folk heroes, although the genuine aspects of their hard-living were never glossed over. Like Dutch Baroque genre paintings, his figures are based on real people. Bingham endowed them with a dignity, however, that has sometimes earned his style the name “Missouri Classicism.”

|

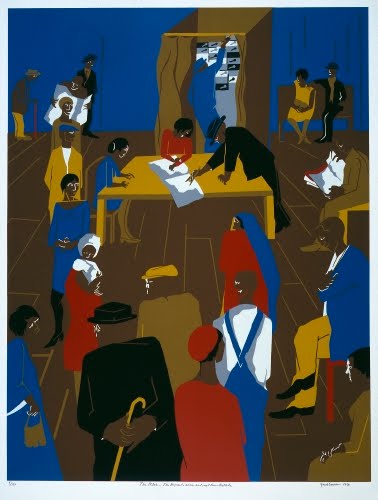

| Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000 US), The Twenties—Migrants Cast Their Ballots, from the Kent Bicentennial Portfolio, Spirit of Independence, 1974, published 1975. Serigraph on paper, 32" x 24 7/8" (81.3 x 63.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum. © 2016 Estate of Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (BMA-466lwars) |

Jacob Lawrence was a keen observer and documenter of the African American experience. His paintings are a valuable historical record of the progress of blacks in the US after the Great Migration. This painting relates the experience of the southern migrants finding it a lot easier to vote in the North than in the South. Despite the passage of the 15thAmendment in 1870, which guaranteed all Americans the right to vote (including African Americans), many southern states passed restrictive laws (such as a land ownership requirement, or a poll tax) to prevent black participation. Unfortunately, aside from jobs and the ability to vote in the North, African Americans still found a lot of discrimination.

The migration (Great Migration) of African Americans from the rural South to northern industrial cities in search of jobs changed the course of history for blacks in America. In cities such as New York and Chicago, the black populations increased dramatically between 1918 and 1925. Cohesive African American communities formed within the cities, and African Americans found a new self-awareness and pride in their heritage. During the 1920s, a significant number of artists were brought together within these large and varied African American communities, something that could not have happened in the rural South. One of the most vital African American communities was in the Harlem section of New York.

The Worcester Art Museum’s copy of this print is currently on view in their exhibit Picket Fence to Picket Line; Visions of American Citizenship.

|

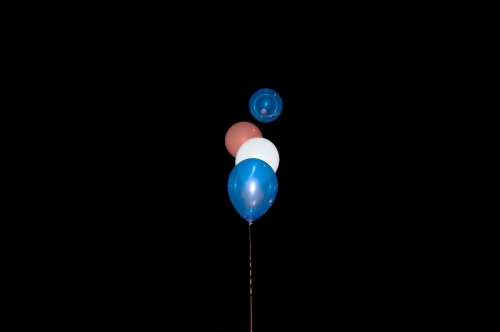

| Zoe Strauss (born 1970, US), Election Day Balloons, Philadelphia, 2008, printed 2011. Digital photograph, Inkjet print on paper, 8" x 12" (20.3 x 30.6 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2016 Zoe Strauss. (PMA-7255) |

We certainly know what this photograph commemorates. It was the election of the first African American president of the US. It was a spectacular moment in American history, and, in typical understated Zoe Strauss fashion, she uses the red-white-and-blue as a symbol for a truly landmark event.

Strauss’ work is reflective of the sophisticated evolution of the Snapshot Aesthetic style of photography. Although the style developed late in the 1800s, it flowered during the 1960s in the hands of such artists as Diane Arbus (1923–1971) and Garry Winogrand (1928–1984). The style mimicked the candid, un-posed, spur-of-the-moment pictures taken by amateurs and middle class families. Interestingly, between the 1960s and the 2000s, the style has been refined to subtly reveal psychological investigation by the photographer.

Works by Arbus opened up a type of personal investigation into subjects that most people see on the street and ignore because it may not be “beautiful.” Strauss’ works address the same phenomenon. Born in Philadelphia, she received her first camera when she was 30. She began photographing the not-well-off areas of Philadelphia, and within ten years was documenting the compelling subject of overlooked realities throughout the country.

While largely self-taught, Strauss’s work displays a sophisticated sense of composition. She is particularly adept at suggestion, and a monumental contrast of positive and negative space. Between 2001 and 2010, Strauss would hold yearly exhibitions of her work in the form of Inkjet prints that she sold for $5 in a makeshift “gallery” under the I-95 underpass in Philadelphia.

Correlation to Davis programs: Explorations in Art Grade 3: intro; A Personal Journey: 1.1, 2.3; A Community Connection: 7.6, Experience Printmaking: 5; Exploring Visual Design: 2, Focus on Photography: 7, Discovering Art History: 15.4, The Visual Experience: 9.5

Comments