Gem of the Month: Tokuyama Gyokuran

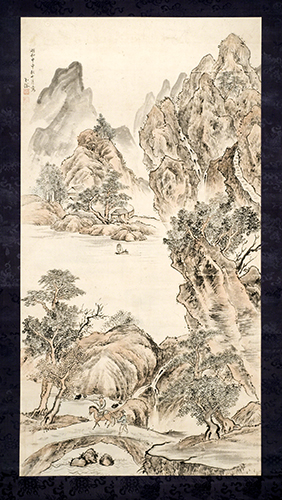

A nice way to spend a summer day: imagining yourself wandering in this landscape by my Gem of the Month, Tokuyama Gyokuran. (As a side note, Chinese scholars considered a painting successful if it invited the viewer to take a mental stroll through the depicted landscape.) I am going to go out on a limb and postulate that she is not one of the women artists of 1700s Japan who “remarkably” had a professional career as a painter. Woman were successful artists in both the East and the West. It’s just that writers of art criticism and art history usually have focused on prominent male artists of their period. Such is the case with Tokuyama, especially since she was married to one of the most famous of all Edo Period “literati” painters, Ike no Taiga. However, records indicate that she was a successful artist before him, and I only stick his work in here (at the bottom) so that you don’t get the impression she learned her vocation from him!

|

| Tokuyama Gyokuran (1728–1784, Japan), Summer Landscape, 1770. Ink and colors on paper, mounted as hanging scroll, 86 5/8" x 45 7/16" (220 x 115.4 cm). © 2019 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-5290) |

The format of Summer Landscape is, overall, a traditional, Chinese-influenced landscape. She reflects the influence of Song Dynasty painting, the so-called "southern school" (Southern Song Dynasty, 1127–1280, considered the “classical” period in Chinese painting) in the gradual diminishing of detail from foreground to background. In the strong diagonal created by the rocks, and the pointed brush work for bamboo, she reflects the influence of Ike.

Tokuyama's landscape represents a transitional period in Japanese landscape, in which the reverence for the amateur scholar painting ideal of “painting what the artist felt” merged with the influence of the Korean “true-view painting,” which advocated for the depiction of specific places. She combined both wet and dry brush techniques in the portrayal of natural elements. This is the only work she signed with a specific date, “eighth month of 1770.”

Gyokuran Tokuyama was born Machi Tokuyama (Tokuyama Machi) in Kyoto, the daughter and granddaughter of two renowned waka (literally Japanese poetry, poems composed in Japanese rather than Chinese) poets. They introduced her to the literati/scholar/amateur artist life early. She was trained in painting by the literati painter Yanagisawa Kien (1704–1758), who also trained the painter Ike no Taiga (1723–1776). The literati style was traditional Chinese monochromatic landscape with personal (“amateur”) expression.

Tokuyama began painting long before she met Ike. They were apparently a well-matched artist couple, living a bohemian lifestyle and painting or playing music together. Despite the fact that they emulated the devil-may-care attitude of the scholar amateurs emphasizing personal expression over canonical Chinese style, both artists made a living selling their paintings.

|

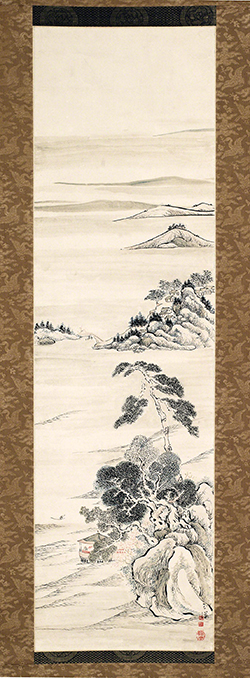

| Tokuyama Gyokuran, Landscape. Ink and color on paper, mounted as hanging scroll, 39 3/16" x 11 7/16" (99.6 x 29 cm). © 2019 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3095) |

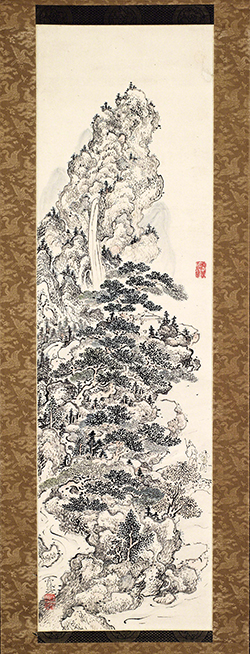

I find Ike’s work much more jittery, with a wobbly linearity that one does not see in Tokuyama’s work. Her work is much more settled and classical than his. I do, however, like the zig-zag line Ike has achieved in the work below, inviting the viewer into the landscape.

|

| Ike no Taiga (1723–1776, Japan), Landscape, before 1752. Ink and color on paper, mounted as a hanging scroll, 39 3/16" x 11 3/8" (99.6 x 29 cm). © 2019 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-3064) |

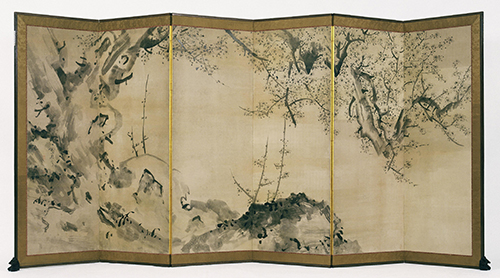

This screen depicts the expressionistic style for which Ike is most renowned. It has the feeling of an impetuous, gestural brush work.

|

| Ike no Taiga, Flowering Plum Trees in Mist, ca. 1750. Ink and gold wash on paper, mounted on wooden frame as a six-fold screen (byobu), 59 13/16" x 141 5/16” (152 x 359 cm). © 2019 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-2746) |

Correlations to Davis Programs: A Community Connection 2E: 4.5, A Global Pursuit 2E: 7.5; The Visual Experience 3E: 13.5; Discovering Art History 4E: 4.4; Discovering Art History Digital: 4.4

Comments