Gem of the Month: Lotus Ten-Panel Screen

In observance of National Korean American Day, which occurred on Friday, January 13th, I dedicate the January Gem of the Month to the singular beauty of Korean art through the centuries. Korean art continues to astound and amaze, including that of Korean American artists who have gifted the U.S. with their unique and compelling vision.

|

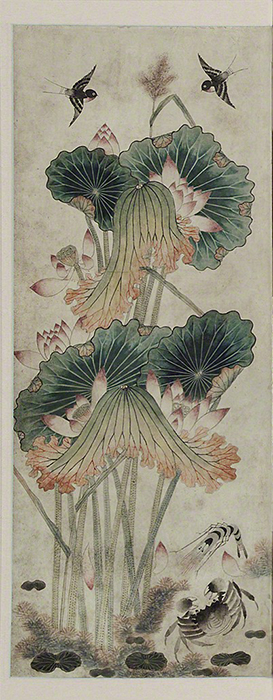

| Korea, Lotus, ten-panel screen, 1800s. Ink and color on paper, mounted on wooden frame, overall: 5' 5" x 11' 3" (167.6 x 343 cm). © 2023 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-7094) |

Just as in China and Japan, fashionable Koreans of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) divided rooms in their homes with moveable screens. In the decoration of these screens, there is an exuberance and exaggeration in the designs that are purely Korean, as seen in the oversized flowers on the Lotus screen panels.

The lotus is a plant with numerous symbolic meanings. It is an ancient symbol of resurrection because the lotus blossom closes at night and reopens in the morning, making it also a symbol of the life-giving sun. It is viewed as a symbol of spiritual purity because the lotus produces beautiful and fragrant flowers from muddy pond water. The Buddha is often depicted enthroned directly on a large lotus blossom. The fully open lotus blossom is therefore a symbol of enlightenment and total self-awareness. In Korea, the symbolism of the lotus took on greater emphasis with the expansion of Buddhism during the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392).

The influence of Confucian rule during the Joseon dynasty infused the lotus with further attributes of the upright and faithful scholar. Confucianism was a spiritual discipline that originated in China. In Chinese, the word for lotus (lian) and the word for uprightness (lian) are homonyms. Scholars who sought to exhibit their scholarly virtue in their homes often installed lotus ponds in their gardens or commissioned lotus paintings like this screen.

During the Joseon dynasty there was a differentiation between professional artists (hwanjaeng-i) and the literati/scholar/amateur artists of the nobility. The hwanjaeng-i were looked upon as inferior to the scholar artists, and their art form faced government rules and regulations. In the 1700s, there were more subtle personal variations on traditional painting styles as Korea experienced a greater degree of independence, largely due to peace in China and Japanese isolation.

The late Joseon dynasty also witnessed the decline of the absolute monarchy and strength of the landed nobility. The merchant class grew in prosperity because of increased foreign trade, creating a new class of art patrons. These patrons were less interested in the professional artists, but were also turned off by the literati concern with the heavily Chinese-influenced landscape painting of the past. However, professional artists cranked out works of art such as screens and portraits to satisfy the merchant class's aspirations to the same luxuries as the nobility.

|

| Korea, Lotus, ten-panel screen (detail of first panel), 1800s. Ink and color on paper, mounted on wooden frame, each panel: 66" x 13 ½" (167.6 x 34.3 cm). © 2023 Philadelphia Museum of Art. (PMA-7094) |

Correlations to Davis programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 1: 4.2; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 2: 1.2, 1.3; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 3: 5.6; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 5: 4.1, 4.2; A Global Pursuit 2E: 4.5; Experience Art: 4.2; Experience Painting: Chapter 4; Exploring Visual Design 4E: Chapters 11, 12; The Visual Experience 3E: 13.6

Comments