Daylight Saving Time Gone: Dusk in Art

Daylight Saving Time ended this past weekend. Everyone is moaning about leaving work when it’s dark. I’m here to prove that there is beauty in the early onset of darkness…with beautiful works of art! We’ll start at dusk for today’s post and work our way to full-fledged night on Wednesday.

|

| Shibata Zeshin (1807–1891, Japan) Crows Flying by Red Sky at Sunset, from the series Comparison of Flowers, ca. 1880. Color woodcut on paper, 9" x 9 5/16" (22.9 x 23.7 cm). © 2019 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-2406) |

We’ll start with the sun just going down, about 4:30 now, right? Although Shibata Zeshin is primarily known for his paintings, especially in lacquer, in the Shijo style—a combination of Western influences with traditional Japanese compositions and subject matter—he also made a living producing woodblock prints.

This was the last great period of the ukiyo-e style. But rather than continue the courtesan and actor prints, Shibata concentrated on traditional nature subjects. As sunsets symbolize the end of life almost universally, crows in Japan are considered divine messengers. Hearing their cry is receiving a message from a departed loved one. Works such as this—asymmetrical balance, contrast of positive and negative space, and open composition—had a major impact on Western artists at the time.

Shibata lived through tremendous cultural and artistic changes in Japan. The US forced Japan open to Western trade in 1854, the Ansei Earthquake of 1855 destroyed much of Edo (Tokyo), and the Meiji “restoration” theoretically put authority back in the hands of an emperor rather than a military dictator (shogun).

Shibata was born in Edo, son of an ukiyo-e print artist who had studied under Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1793). Shibata began an apprenticeship at age 11 to a lacquer artist. At 13 he was apprenticed to the artist Suzuki Nanrei (1775–1844) to learn how to draw. While studying under Nanrei, he acquired the name Zeshin (“true artist”). He also studied in Kyoto, where he studied Japanese history and Buddhist traditions including the tea ceremony, waka and haiku poetry, and philosophy.

|

| Claude Monet (1840–1926, France), Waterloo Bridge, London, at Dusk, 1904. Oil on canvas, 25 7/8" x 40" (65.7 x 101.6 cm). © 2019 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. (NGA-P0999) |

I was lucky enough to see nine of Claude Monet’s forty paintings (more versions than of either the Houses of Parliament or Charing Cross Bridge, his other two London series) of Waterloo Bridge at the Worcester Art Museum earlier this year. Seeing them all in one room is a thrill if you’re a maniac about color the way I am. This one was particularly awesome to see close up, there are touches of cobalt violet for the deep shadows.

While other artists would use a muted palette to depict fog and smog, Monet’s palette fairly exploded with a whole range of colors, depicting the bridge at all times of day from his room at the Savoy Hotel between 1899 and 1901. He had been charmed by the vistas in London when he first visited in 1871. The late paintings of Monet suggest Turner in the fog-flattened silhouette of the buildings. However, Monet achieved a freedom of form and dynamic color he probably had not imagined in 1871.

Compared to his Rouen Cathedral paintings at the National Gallery of Art, the forms in this work are much more dissolved and suggestive, with more attention paid to the richness of color than the nuances on physical surfaces. As in his other series, water plays a key role in the bridge works. Similar to his Vetheuil and Giverny works, the suggestive forms cause the viewer to question not only where the horizon line is, but also which part of the composition is reflection.

|

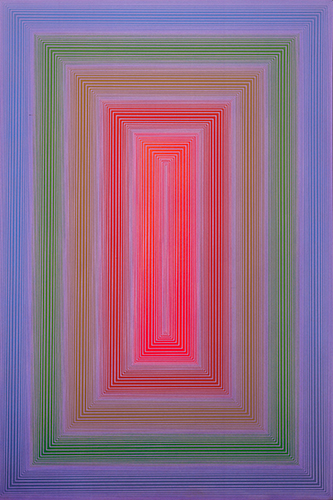

| Richard Anuszkiewicz (born 1930, US), Dusk, 1970. Acrylic on canvas, 72" x 47 15/16" (182.9 x 121.9 cm). Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY. © 2019 Richard Anuszkiewicz/Licensed by VAGA in Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (AK-115azvg) |

I would personally love to see these colors at dusk. Richard Anuszkiewicz was one of the few pioneer American Op Artists in the groundbreaking 1965 show The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Dusk from shortly after that exhibition is characteristic of his work that compounds the basic geometry of innovative abstractionist Josef Albers (1888-1976) with radiating parallel lines in complementary colors. In this painting, red and green are the complementary colors, with green parallel lines piercing red and magenta cubes.

Anuszkiewicz's use of line activates the picture plane and causes the eye to separate the green from the red. Outside of the inner red rectangle, the green lines turn blue, causing the eye to see purple as it travels through the outer red rectangle. The radiant lines make it uncertain whether the central green rectangle is receding or projecting, and ironic twist on the Hans Hofmann idiom of “push and pull” color.

Anuszkiewicz, born in Pennsylvania, was encouraged by his father in an early interest in being an artist. While studying at the Cleveland Institute of Art (1948–1953), he became interested in abstract painting, with particular interest in the underlying design process of creating a work of art. He subsequently studied under Albers at Yale. He was influenced by Albers’s geometric abstractions, which explored the role color combinations played in optical perception of abstract works, such as the Homage to the Square paintings. While at Yale, Anuszkiewicz reduced his paintings to combinations of flat, geometric forms.

Anuszkiewicz received a bachelor’s in science at Kent State University in Ohio (1955–1956). During his studies, he learned the scientific foundations of color theory and how the human eye perceives colors. This understanding was augmented by his previous studies of theories by Post-Impressionists and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) about how the eye perceived different colors placed next to each other to build form. His interest in the possibilities of geometric abstraction that contained a vibrant surface without the gestural brush work of Abstract Expressionism led to his mature style in 1957.

Comments