World Watercolor Month: Kawakami Ryoka

Japanese artists have been proficient in water-soluble media for centuries. Early forms of water-soluble media included gofun—crushed white clam shells mixed with water and pigments—and diluted ink painting. Watercolors became popular with Japanese artists during the Meiji period (1868–1912), influenced by the introduction Western art techniques after the 1850s. While watercolor may have been Western influenced, the subject matter remained firmly in the Japanese tradition.

|

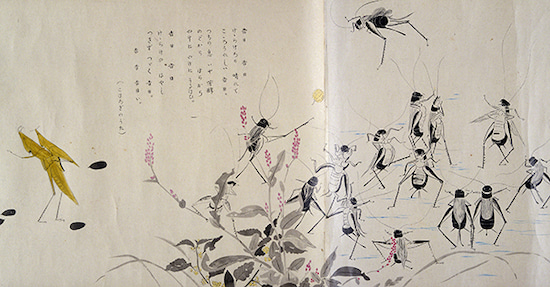

| Kawakami Ryoka (1887–1921, Japan), Praying Mantis and Water Bugs, close-up of section of Wildlife Friends handscroll, ca. 1918. Ink, opaque watercolors and possibly lacquer on wove paper decorated with mica, overall: 8 7⁄16" x 17' 7" (21.4 x 523.2 cm). Image © 2025 Brooklyn Museum. (BMA-1177A) |

Kawakami Ryoka’s Wildlife Friends follows the ages-old tradition of Japanese reverence for nature, which dates back to works of “animals acting like people” paintings from the Heian period (794–1185). Kawakami treated the subject in the same light-hearted manner using Western painting techniques. The Japanese reverence for nature includes an appreciation for all manner of insects.

This section depicts a praying mantis mother carrying a baby on her back. A group of water bugs watches a fellow water bug kick a gourd (or seed pod?). The praying mantis is a symbol of autumn and the circle of life (hence the baby). Water bugs (relatives of cockroaches) are considered hard workers, part of a family of insects (orthoptera) that are musical and sometimes collected and kept as pets in cages.

Many Japanese art forms have decoration or shapes based on the natural world, reflecting the Shinto belief in the importance of the seasonal succession of seed time and harvest. Buddhism, too, teaches that people should try to achieve harmony with nature. This reverence goes back through the entire history of Japanese painting, particularly landscape painting.

The Japanese reverence for nature manifests in painting in a myriad of explorations of the natural world, often with humor. As early as the Heian period, there were scroll paintings that depicted animals and insects acting like people, often satirizing Buddhist figures. This humorous genre of Japanese art has persisted to the present day.

Major changes took place in Japanese art during the early 1900s. This was not because the Japanese government was striving to become a Western-style industrialized power. Rather, Japanese artists were increasingly exposed to Western modernism. Between 1910 and 1923, the magazine Shirakaba (“White Birch”) introduced Japanese artists to the work of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), and other progressive painters from Europe. This allowed many young painters to study Western painting without going there. It also encouraged Japanese artists that they, too, could rebel against the established, entrenched "tradition" in Japanese art.

Kawakami was a major force in pushing for progressive approaches to painting in Japan already in 1905 when he studied Western-style painting (yō-ga). At the time, there were two trains of thought on Western influence in Japanese art. The yō-ga studied Western methods such as watercolor, oil painting, and Western printmaking techniques applied in traditionally Japanese compositions. The hakuba-kai imitated Western styles and compositions with Japanese subjects. Although Kawakami painted in a Fauvist style, he also produced works in the nihon-ga or Japanese style.

Correlations to Davis Programs: Explorations in Art Kindergarten 2E: 2.1, 2.2, 2.3; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 1: 4.1, 4.3; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 3: 5.3; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 4: 4.3; Explorations in Art 2E Grade 6: 2.8; Experience Art: 4.1, 4.2; A Global Pursuit 2E: 7.4 p. 199; Discovering Drawing 3E: Chapter 8; Focus on Photography 2E: pp. 317–318

Comments