Hispanic Heritage Month: Óscar Muñoz

Hispanic Heritage Month celebration was initially celebrated for a week starting in 1968, and was expanded to a month in 1988. The great artistic heritage of Mexico, Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, and South America have been celebrated by American Latinos artistically in a big way since the fabulous mural movement from the late 1960s into the early 1970s. This week we celebrate a unique Colombian artist whose works are quite stunning and different: Óscar Muñoz.

|

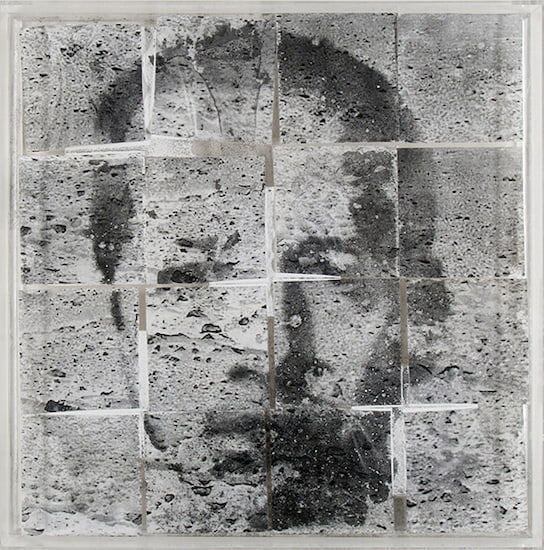

| Óscar Muñoz (born 1951, Colombia), Dry Narcissi / Narcisos Secos, from the diptych Narcissi (Narcisos), 2010. Charcoal powder on printed paper mounted on Plexiglas, 20 ⅛" x 20 1⁄16" x 1 ½" (51.1 x 51 x 3.8 cm), archival box: 20 ½" x 20 ½" x 1 ⅝" (52.1 x 52.1 x 4.1 cm). Image courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2025 Óscar Muñoz. (PMA-6590) |

Muñoz has explored the medium of photography continuously as the basis for his drawings. The overriding emphasis on transition and deterioration has played a major part in how he combines the use of charcoal and photography. The series called Narcissi (Narcisos)—the plural of narcissus, a flower—has been instrumental in his quest to dematerialize the support of photographic images executed in charcoal on a variety of temporary supports.

In the Narcissi (Narcisos) series, Muñoz executed charcoal portraits based on photographs onto printed or plain paper, attached to a Plexiglas sheet then suspended in a closed box over a thin layer of water. As the water evaporated, it affected the density of the charcoal as well as the integrity of the paper support, thus altering the final image. Ultimately, as a symbol for death, the paper images often crumble to dust from the action of the evaporating water.

This untitled Narcissi (Narcisos) was acquired by the Philadelphia museum after the action of evaporation had already occurred. Its effect on the paper and the charcoal is evident in bleeding lines and water marks. The portrait is the face of one of the many thousands of los desaparecidos (the disappeared) of Colombia who vanished without a trace between the 1970s and the 2000s due to various urban, government, and social problems.

A generation of artists born after World War II (1939–1945) from South America have achieved international recognition, partly as a result of their choosing to live and work in their countries of birth. During the mid-1900s, artists from countries such as Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Cuba and Mexico felt obliged to emigrate either to Europe or the United States to further their careers. Until that time, figurative, academic art was dominant in Colombia.

By the 1980s, the new generation of artists had learned what they could in Europe and America, but returned with that inspiration to their native Colombia. Where New York and Paris were once viewed as the dictatorial centers of the “art world,” the world artistic community now recognizes the validity of art made outside of those centers, accepted on its own terms. This includes radical experiment in media that help express indigenous society and issues.

Muñoz was born in Popayan, Colombia. He studied at the School of Fine Arts in Cali in the 1970s. Even as a student he fascinated with photography and transferring it into drawing. He also experimented with charcoal extensively. Although his work did not include photography specifically, it was a central element to his graphic work. In the pervasive atmosphere of kidnappings and killings in Colombia, Muñoz's work became focused on faces as reflections of memory and mortality. The use of ephemeral materials heightened this sense.

Muñoz emerged prominently on the Colombian art scene with a series of large, photo-realistic drawings in charcoal on paper that reflected neglected or deteriorating spaces, reflecting urban life in Cali. In the 1980s he gradually abandoned paper as his primary support and began to experiment with new techniques of drawing and printmaking. Some of his experimental supports included plastic shower curtains and Plexiglas, on which he printed his drawn images. In 2006 he established the art and cultural center Space for Doubts, a center for young artists to participate in a dialogue about art and ideological concerns.

This other half of the diptych shows how the evaporation of the water has drastically affected the state of the paper support:

|

| Óscar Muñoz, Dry Narcissi / Narcisos Secos, from the diptych Narcissi (Narcisos), 2010. Charcoal powder on printed paper mounted on Plexiglas, 20 ⅛" x 20 1⁄16" x 1 ½" (51.1 x 51 x 3.8 cm), archival box: 20 ½" x 20 ½" x 1 ⅝" (52.1 x 52.1 x 4.1 cm). Image courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2025 Óscar Muñoz. (PMA-6591) |

Correlations to Davis Programs: Explorations in Art 2E Grade 5: 1.2, A Community Connection 2E: Unit 2, 2.3 Studio Exploration; A Personal Journey 2E: Unit 9, 9.1; Discovering Drawing 3E: Chapter 7 Portraits; Davis Collections: Latinx Art, Central and South America

Comments