Artist Birthday: Käthe Kollwitz

Unequaled among the German Expressionists are the gritty, powerfully heart-felt drawings, lithographs and woodcuts of Käthe Kollwitz. Much of her subject matter concerned working class women, mothers and widows, particularly after the loss of her son Peter (1896–1914) in World War I (1914–1918).

Artist Birthday for 8 July: Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945, Germany)

Käthe Kollwitz is undoubtedly most renowned for her graphic works.

|

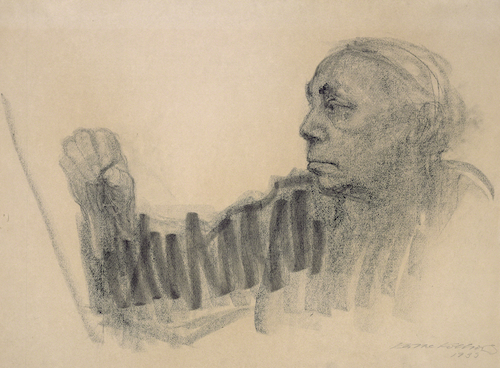

| Käthe Kollwitz, Self-Portrait, Drawing, 1933. Charcoal on brown laid paper, 47.7 x 63.5 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington. © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (NGA-P0762kzars) |

Kollwitz made more than one hundred self-portraits throughout her career. She faced many tragic personal losses in her life, which is a likely reason that mortality became a major theme in her art. Her self-portraits were unflinching depictions of a woman whose face was haggard from her emotional trials. And yet, these self-portraits also portray a woman who was never defeated by life’s blows.

Self-Portrait, Drawing is one of the rare pieces in which Kollwitz expresses her pride as an accomplished artist. Its gestural lines are as emphatic and expressive as any in her works that were concerned with suffering and death. The haggard face and grim look of determination reveal a woman who is driven to produce her art by an inner passion for truth.

Kollwitz ranks with Rembrandt for the importance of the subject of self-portrait in her body of work. Before the early 20th century, self-portraits served to represent the artist’s status and leave a record of their career. With the simultaneous advent of psychoanalysis and Expressionism at the turn of the 1900s, artists’ self-portraits often began to take on psychological or emotional implications, dealing inevitably with mortality.

In the early 1900s, Expressionism originated in Northern Europe as an offshoot of art movements in the late 1800s. The movement emphasized Romanticism, expressive color, or symbolic (rather than representational) subject matter, and its objective was to communicate the artist’s feelings and to elicit an emotional reaction from the viewer.

Kollwitz was one of the leading graphic artists in the first half of the 1900s. Her father recognized her talent for art at an early age, particularly in drawing, and encouraged her to pursue a career in art. She received her first training at 14 in her native city of Königsberg under an engraver in a conservative and somewhat academic style. She continued her education in Berlin where she encountered the work of Symbolist artists, which impressed her. Kollwitz was influenced more by the graphic techniques she saw in Berlin, rather than by any particular style. She also studied sculpture in Paris.

Kollwitz’s emphasis on human suffering, particularly suffering experienced by women, demanded realism. Her marriage to a doctor who practiced in a poor quarter of Berlin exposed her constantly to the struggles of the poor. Personal tragedies, including the death of a son in World War I, gave her body of work an overall somber element. Another influence on Kollwitz was the work of Edvard Munch (1863–1944), a Norwegian Expressionist whose work emphasized the plight of humanity. Although Kollwitz also became a competent sculptor, she preferred the graphic medium, which had a strong tradition in German art going back to the Renaissance (ca. 1400s–1600).

Kollwitz first exhibited in 1893 at the Free Art Exhibit in Berlin, where she continued to show her work until the Nazis banned it in 1936 as "degenerate". Her graphic works were published in many socially aware magazines, including the satirical Simplicissimus. Although she was not interested in contemporary art movements such as German Expressionism or French Fauvism, Kollwitz was not insensible to the emotional impact possible with the use of jagged slashing lines, compressed compositions, and stark contrasts in dark and light.

Correlations to Davis programs: Experience Art, Unit 3 Identity, 3.5 -- Making Connections, Art History; Discovering Drawing 3E, Chapter 1, What is Drawing? -- Drawing as Expression; Davis Collections, Women Artists 1900s

Comments